The American style of tipping your server emerged during reconstruction and took decades to be accepted. But it became entrenched during Prohibition and is now a deeply ingrained social norm.

It is safe to say that William Scott was no fan of tipping. In his book, “The Itching Palm,” Scott called tipping “un-American” and “flunkeyism” that “borders on bribery” and amounts to “legalized robbery.” He also wrote, “someday, somehow, it will be uprooted like African slavery.”

That prediction has not quite proven true. Tipping has become more ingrained and more American in the more than 100 years since Scott published his treatise against the practice. What once had been considered a largely European practice has been fully adopted by Americans and, perhaps unsurprisingly, taken to an entirely different level.

Americans seem to both love and loathe the tip. Few societal norms generate quite as much antipathy as the practice of adding an extra 20% to a restaurant bill. And yet few seem so difficult to remove.

Inside restaurants, tipping has become both a management tool and a method for operators to keep wages low. Customers tip out of a sense of duty and of generosity, but also so they can avoid embarrassment. Tips are sometimes based on the looks or race of the server rather than on the level of service provided.

Government rules have enabled tipping, even as some states push to end it. And yet, the war for talent has led more types of restaurants that at one time actively avoided tipping to adopt the practice, while the expected amount for tips has gradually risen with the adoption of suggested tipping practices on receipts. Get rid of the tip? If anything, the practice is more ingrained than ever.

Reconstruction

When it comes to the history of tipping, much of the attention has tied the practice to slavery. In reality, the origins are more complex, tied to medieval European nobility, post-Civil War reconstruction and prohibition. Its rise is directly tied to the emergence of the restaurant as an industry.

Tipping may date back to the Roman era, but most sources trace it back to medieval Europe, when wealthy visitors to homes would leave tips for servants who provided good service. The word “tip” dates to the 17th century, when London taverns and coffee houses would put signs saying, “To Insure Promptitude” alongside boxes or bowls where customers could leave an extra coin for faster service.

Tipping was almost nonexistent in the U.S. before the Civil War. But wealthy Americans, visiting Europe, brought the practice to the U.S. in the mid-1800s, unsurprisingly eager to mimic European customs. But it took root as a business strategy during reconstruction.

Some hospitality companies started to use freed slaves, paid them low wages, then encouraged customers to leave tips.

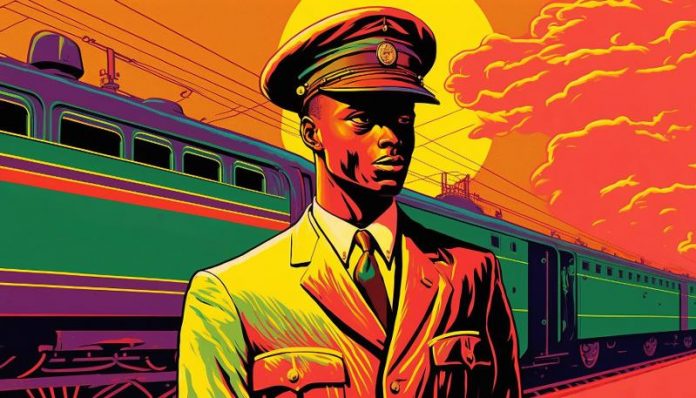

George Pullman founded The Pullman Co. in 1859 and started operating luxury sleeping cars on the country’s growing network of railways. In 1868, Pullman began hiring Black men, most of them former slaves, to serve as porters. He considered them to be perfectly trained servants.

Pullman paid them miniscule wages, about $27.50 per month in 1916, according to Scott. That’s the equivalent of $814, which is less than the equivalent today of $10,000 per year, though they often worked 400 hours per month. They were treated harshly and often subject to abuse. But Pullman encouraged wealthy passengers of those luxury cars to leave them tips.

The rail car company played a major role in the spread of tipping. “The Pullman Co. stands in the public mind as the leading exponent of tipping,” Scott wrote. “It certainly is the largest beneficiary of the custom.” Scott estimated that, in 1916, tipping saved the Pullman Co. $2.5 million in annual payroll, or about $75 million adjusted for inflation.

Numerous other companies adopted similar practices and by the turn of the century, tipping had become common.

Opposition and prohibition

The emergence of tipping in the late 1800s was met with often fierce opposition. It was often derided as un-American, running against the country’s allegedly egalitarian ideals, and was often likened to a bribe, sometimes by the business owners themselves. Seven states, most of them in the South, banned the practice outright.

“In a restaurant where the employer has thus shifted the cost of waiter hire to the shoulders of the public, the patron who conscientiously objects to tipping has not the slightest chance in the world of a square deal in competition with the patron who pays tribute, although he pays as much for the food,” Scott wrote.

“A man must be a born snob who enjoys the servility and likes to revel in the bought smile of porters … who sell civility by the pennyworth,” the New York Times wrote in 1884.

But the practice was stuck by the early 1900s. Two events solidified the status of tipping in the U.S.

First, hotels that served as the nation’s first restaurants separated their meal services from the bills of hotel guests, so meals were billed separately. Hotels viewed this as more profitable, but it also led to a shift in thinking among hotel owners, according to a 2013 study by the University of Saskatchewan and published in the International Journal of Management.

Hotel owners opposed the practice when meals were included in the hotel bill, because customers sometimes gave tips to get more food out of servers. When the shift was made to a separate bill, the tips could be used to supplement wages.

Prohibition sped that shift.

The nationwide ban of the sale of alcoholic beverages, which started in 1920, had a wide-ranging impact on society. According to the Journal of Management study, prohibition led many hotels to convert bars into “lunch rooms” that sold meals to anyone. Hotel owners were more tolerant of tipping because customers ordered meals from a menu, so it seemed less like a bribe.

The University of Saskatchewan study noted that tipping grew more and more accepted in industry journals, notably Hotel Monthly. In a 1921 essay in the publication, Chicago journalist Wallace Rice called tipping patriotic. The article was titled, “Proving that tipping is good American today.”

The state laws against tipping all proved ineffective. By 1926, each of the states that banned the practice had rescinded those rules.

In 1938, President Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which established the first minimum wage, 25 cents per hour. But there was no minimum for tipped wages. In so doing, Congress codified the tipping practice. It wouldn’t be until 1966 before it would pass a minimum for tipped workers.

A social norm

These days, tipping is a pure social norm at restaurants. According to the Council of Economic Advisors, 98% of customers at full-service restaurants leave a tip. Americans leave more money for their restaurant servers than any other country.

The National Restaurant Association estimates that $324 billion was generated at full-service restaurants last year. That suggests consumers at those restaurants paid anywhere from $35 billion to $60 billion depending on the percentage of dine-in sales last year and the number of tips left for other forms of service at those restaurants.

That’s not including the tips left to pizza delivery drivers or the growing number of counter-service employees who are getting tips.

Various factors that have little to do with service quality play a role in the amount of the tip. According to a University of Nevada-Las Vegas study, the amount of tip a customer leaves may be a result of good service. But other factors are at play, too, including looks if the server is a woman; the server’s race; time of day; location of the restaurant; and simply the customer’s attitude toward the practice.

Critics of tipping have long pointed out these flaws, while arguing that it perpetuates inequality inside the restaurant and enables operators to pay low wages. And some restaurant owners, notably the New York City restaurateur Danny Meyer, have publicly moved away from the practice, with mixed results. For the most part, however, moving the country away from tipping and more toward a higher set wage has proven more difficult than it sounds.

Meanwhile, the practice has spread from full-service restaurants to limited-service operations. Proponents such as Jersey Mike’s and Smashburger find that a communal tip jar can raise hourly income by $4 to $6 an hour. Having a tip option was the second most frequent request the Sonic drive-in chain fielded from customers. It is now complying, using the brand’s app as the means. Starbucks, as part of its effort to drive up income for its employees, is also implementing tipping.

One hundred years after Scott’s book, in other words, this former European practice has become uniquely American. Far from being uprooted, its roots are deeper than ever.

Published By: Restaurant Business