A chef and food writer takes a hard look at the Mammy stereotype, the rare outliers who have achieved recognition for their cooking, and the inequity that still prevents most Black women from owning restaurants.

There’s a moment in the 2009 animated Disney film The Princess and the Frog, when the main protagonist, Tiana, a New Orleans-born Black woman, is on the precipice of realizing her lifelong dream of owning a restaurant.

Then, a real estate agent, Mr. Fenner of Fenner & Fenner, who had been poised to sell Tiana her coveted restaurant space, tells her she has been outbid.

“A little woman of your . . . background would have had her hands full trying to run a big business like that. You’re better off where you’re at,” he tells her.

It doesn’t take much imagination to intuit what function that pregnant pause, and the word “background,” have in the scene. Disney, as much a mirror on American life as any media, was punctuating a disturbing American credo in that scene: the U.S., as represented by Mr. Fenner, thinks Tiana is better off as a laborer, nothing more.

After Mr. Fenner breaks the news, Tiana takes her place back behind the catering table at the Mardi Gras ball where she’s serving her specialty beignets. She trips and falls, all of the beignets she baked for the event go flying, and our heroine sits dejectedly in a dustbowl of powdered sugar and sorrow.

In his foreword to The Jemima Code, author Toni Tipton Martin’s presentation of more than 150 African American cookbooks, journalist John Edgerton wrote:

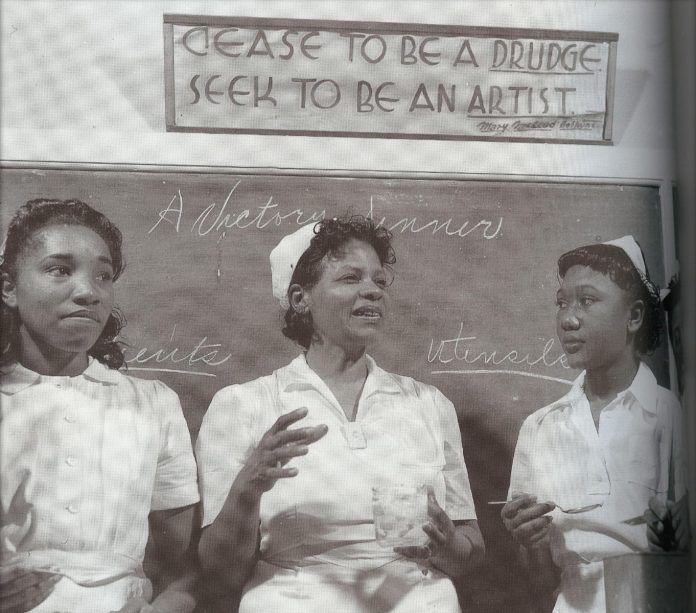

“Throughout 350 years of slavery, segregation, and legally enforced white supremacy, the vast majority of women of African ancestry in the South lived lives tightly circumscribed [to] . . . domestic kitchens. To them fell the overarching responsibility for the feeding of the South, as well as the duty of birthing and nurturing replacement generations.”

In the collection, Tipton Martin lays out another brutal conundrum: the image of the Black woman chef embedded in the cruel stereotype and barbarous invention of racism and in the caricature of the Mammy—a deceit that functions, in part, to bury the rich culinary gifts that Black women have given American cooking.

After years working as a chef, I did not see myself reflected in the food industry. Around four years ago, Tipton Martin’s book opened up my own personal search for other Black women in food.

I quickly learned that I was not alone in my search. Modern American cooking enthusiasts have long been wringing their hands over the question of what “American” food actually means, and a growing number of chefs are circumventing the Eurocentric answer to that question and revealing actual Native American ingredients and cookery—ancient traditions hidden and all but destroyed by colonialism.

“Of the roughly one million restaurants in the country, about eight percent are Black-owned. About 2,800 are owned by Black women. That’s less than a third of one percent of all American restaurants.”

But the millions of Black women who picked up those Native ingredients and applied both the intelligence and traditions of Africa and those of Europe that were imposed on them have yet to garner rightful recognition in the pantheon of the American professional kitchen. Their toil and intellectual property have been as dismissed and concealed as that of any slave, their names sacrificed and lost to the American project.

Of the roughly 1 million restaurants in the country, for instance, about 8 percent are Black-owned. About 2,800 are owned by Black women, according to 2019 Census information. That’s less than a third of 1 percent of all American restaurants.

Invisible Domestic Work

In his 2015 profile of Southern cooking doyenne Edna Lewis, journalist Francis Lam wrote,

“The elite homes of Virginia, going back to the days when the Colonial elite socialized with French politicians and generals during the Revolutionary War, dined on a cuisine inspired by France. It was built on local ingredients—many originally shared by Native Americans or brought by slaves from Africa—and developed by enslaved black chefs like James Hemings, who cooked for Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. Because this aristocratic strain of Southern cuisine was provisioned and cooked largely by black people, it came into their communities as well, including Freetown.”

Freetown was Lewis’s hometown, a Virginia homestead built by a community of formerly enslaved people, including her grandfather.

For anyone concerned with the legacy of the Black chef in America, James Hemings and Edna Lewis are familiar names. Lewis left Freetown during the Great Migration for Washington, D.C. and then New York, where she found work first as a domestic and then eventually as a cook in stylish restaurants, which led her finally to her own restaurant and a cookbook deal.

In her cookbook The Taste of Country Cooking, Miss Lewis, as she was known, writes in almost ecstatically loving terms about her childhood in Freetown. She recalls details like the “moist smell of chickens hatching” and “the first asparagus that appeared on the fence row, grown from the seed the birds dropped.” Along with hundreds of others, these memories recall a life made of not just four seasons, but the many seasons that arrive each year, and with them, the resulting cuisine that was so endemic it was sacred.

But by the time she was 15, Lewis left Freetown as part of the Great Migration, an event often described as millions of people moving for a “better life.” In reality, 6 million African Americans fled the South in an effort to get away from white terrorism: the lynching and indentured servitude that made “free” life not much better than enslavement, and the destruction of their homesteads and farm properties to a degree that often resulted in starvation.

Miss Lewis likely didn’t leave her community as a child—for a place completely unknown to her—because she was in search of a better life. When she did leave, her dressmaking skills put her in circles with white socialites, including an antiques dealer with whom she eventually became a partner in her first restaurant.

Tipton Martin, who had a chance to meet Miss Lewis before she passed away in 2006, told her that the world needed to know that there were a lot more people like her—they have just been invisible, hidden. Miss Lewis responded in a letter: “Leave no stone unturned to prove this point. Make sure that you do.”

So what of the millions of other women constrained to the American kitchen for 350 years, and what of their bequest? What of their descendants? Where are our restaurants and our book deals?

Published By: Civil Eats